The potentially stolen wind chimes and the symphony of chairs

The potentially stolen wind chimes

On a scorching hot summer day in Shitang Village, I found myself in an impromptu conversation with the children on the difficult topic of governance.

For two days, we had been making wind chimes with the children, using bamboo pieces, seeds, and recycled plastic bottles. Our goal was to add an artistic touch to the playground we had co-designed two months earlier. We aimed to make the experience as whimsical as it was educational for the 12 or so children, aged 6 to 12, who participated. We mimicked the sounds of rain on the ground, went on a scavenger hunt for sustainable materials, painted seeds while discussing emotions, and finally, chose two trees in the playground where the wind chimes would be hung.

As we approached the final touches, I asked the group: "How will we prevent people from sabotaging the wind chimes or taking them home?"

The children offered two responses:

"We can have two people watch over them."

"We can install security cameras and monitor them at the village committee."

(One child even suggested disguising a camera by gluing it onto a wind chime.)

After I explained that we couldn't afford either option, the children expressed disappointment, certain the wind chimes would be sabotaged.

We tried to steer the conversation in another direction. One volunteer asked, "What if we tell everyone how long it took to make them, and how much effort we put into it?" I followed up with an introspective question: "If we went to all this trouble and believed the wind chimes are so beautiful, why didn't we take them home instead of hanging them in the park for others to play with?"

The children responded that they wanted to share. I then suggested that sometimes people might damage things out of a desire to interact with them. So, what if we provided fun ways to engage with the wind chimes?

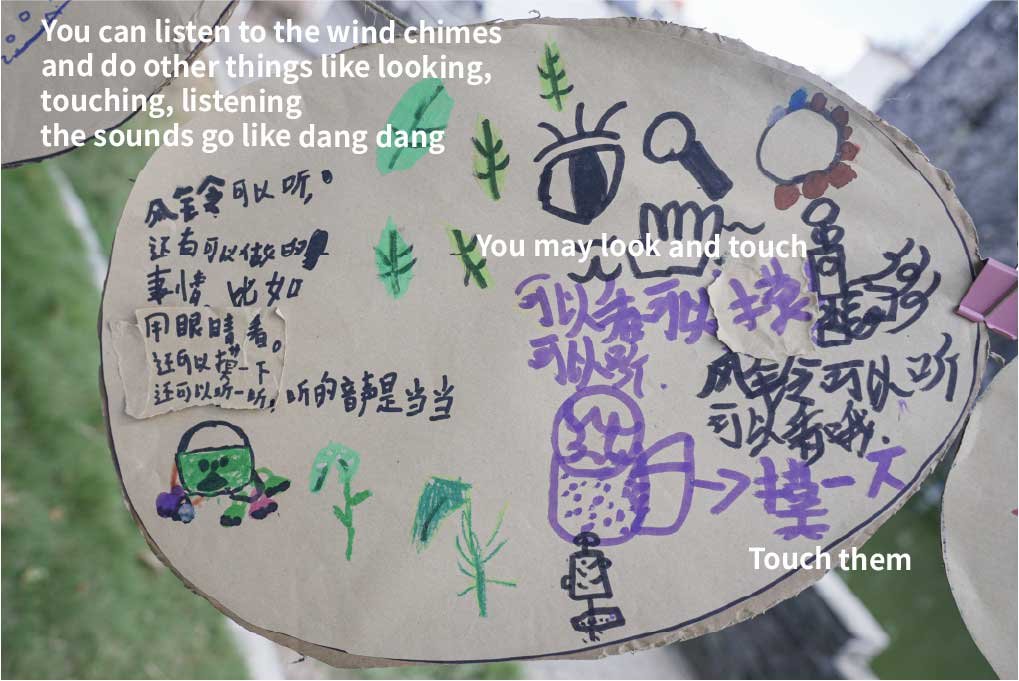

We then asked the children to design signs to place near the wind chimes. They first noted their ideas on sticky notes, and then turned them into large signs.

And these are what they came up with.

I was particularly touched by the poetry in the following expression:

When there is wind,

Please listen carefully

to the sounds we prepared for you.

Followed by a warning:

Do not damage.

The next day, we asked the children to turn the contents of the sticky notes into real signs.

But will this work? Will these sincere messages actually prevent the wind chimes from being taken?

When I ask myself this, a more uncomfortable question lingers in the background: Why are we so convinced that residents of the village are likely to take or damage things that are "obviously" public? Is this distrust warranted?

To be fair, just the day before, a wagon we used for construction was "taken" in the middle of the night, causing distress for the construction team the next morning.

It was not uneasy to accept a common notion that "people in the villages like to take things."

Towards the end of the event, we comforted the children with the thought that they now have to know-how to organize their own wind chime-making activities in case some go missing.

How long will the wind chimes last? I left the village deciding to let this be an experiment.

Symphony of chairs

A few days later, at the invitation of local officials, I went on a trip to visit nearby villages, seeking opportunities to co-design more local play spaces.

When we entered one village, we were greeted by a group of older men and women chatting casually under a large shed—a simple, sheltered public space common in many villages. Recognizing the village chief who was leading us, the group warmly called us over, with two aunties immediately offering homemade pickled leek in plastic bags.

What caught my attention was the variety of seating in the shed. Around the periphery were park benches, while the central space was filled with an eclectic mix of stools and dinner table chairs—some self-made, some factory-made, some plastic, and others wooden. There was even a nightstand among them.

Noticing my interest in the chairs, the uncles and aunts assumed I was looking for a place to sit, and they eagerly competed to offer me a spot next to them.

I made a point to sit in as many different spots as I could before it was time to go. Despite my trouble understanding Hakka, I could tell I was warmly welcomed.

As I was leaving, I couldn’t help but think about the diverse seating arrangements. Besides the park benches that looked like a public purchase, each other piece must have been brought there, one by one, over time, from different households.

In a village, people don’t just take things; they also bring them, I thought.

Connecting what is mine and what is ours

The "potentially stolen" wind chimes and the symphony of chairs made me see ownership in a village in a more dynamic and blurred light.

Could ownership be a fluid concept?

In *"From the Soil,"* Fei Xiaotong, a pioneering Chinese sociologist and anthropologist, discusses the blurred boundaries between private and public lives in rural China, using the metaphor of ripples in water to illustrate the concept. He explains that in traditional Chinese rural society, an individual's social influence and obligations extend outward like ripples, starting from the self and radiating through family, kinship, and the broader community.

These ripples represent varying degrees of intimacy and responsibility, where the closer the relationship, the stronger the social bond and obligation. Unlike in Western societies where there is often a clear distinction between public and private spheres, Fei argues that in rural China, these boundaries are fluid and overlapping. Social interactions and responsibilities are not confined to a strict public or private domain but instead are shaped by the context of relationships, which can shift and overlap depending on the situation. This creates a more intertwined social fabric where personal and communal interests are closely linked.

If the distinction between private and public is seen as a gradient rather than a strict boundary, the "taken" wind chimes could be viewed as moving along this continuum—shifting from public property to something that temporarily enters a private domain, only to potentially return to the public space transformed.

The children's idea captures this fluid relationship:

"If you damage or steal one, you'll have to make the most beautiful one and bring it back to us."

In this perhaps overly idealistic view, the wind chimes, like the chairs, aren't just objects to be protected but catalysts for interaction, reinforcing the interconnectedness of public and private realms.

And how will we protect and nurture this interconnectedness?